https://apologeticspress.org/the-dead-sea-scrolls-and-the-bible-5741/

The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible

[EDITOR’S NOTE: AP auxiliary writer Dr. Rogers is the Director of the Graduate School of Theology and Associate Professor of Bible at Freed-Hardeman University. He holds an M.A. in New Testament from Freed-Hardeman University as well as an M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Hebraic, Judaic, and Cognate Studies from Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.]

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls is widely regarded as the greatest archaeological discovery of the 20th century. From 1947 to 1956 about 930 scrolls were found in 11 desert caves near Qumran, a site about 12½ miles southeast of Jerusalem. Other discoveries were made in about 11 other sites in the vicinity of the Dead Sea, but no place yielded the number of manuscripts as Qumran. The Qumran scrolls span four centuries, from the third century B.C. to the first century A.D., and are written in four languages, Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, and Nabatean, in addition to discovered coins having Latin inscriptions. The Dead Sea Scrolls are important for the Old Testament in at least two major ways: (1) they allow us access to Old Testament manuscripts over 1,000 years older than we previously knew; and (2) they provide information about the formation of the Old Testament canon of Scripture.

The Discovery and Publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The story has been told often.1 A Bedouin shepherd threw a rock into a cave, heard a crash, and discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls. This story is not entirely true. First of all, the broken jar and discovery of the cave took place two days before the first scrolls were found. There was not one Bedouin shepherd, but three. One threw the rock, and another entered the cave two days later without the prior knowledge of his partners. The shepherds took only a few scrolls, and they had no idea what they were and how much they were worth. The scrolls removed from what became known as Cave 1 were the “Great Isaiah Scroll” (1QIsaa), the Habakkuk commentary (1QpHab), and the Community Rule (1QS).2 These were slightly damaged in transportation before they could be sold to a dealer of antiquities, and to a Syrian Orthodox monastery.

When the number and value of the scrolls were determined, other caves continued to be looted and their contents sold by the Ta‘amireh tribe to which the shepherds belonged. Once the importance of the scrolls was determined, both scholars and governmental organizations (initially, of Jordan, and later, of Israel) became involved in discovering additional caves and conducting formal excavations. The site of Qumran was excavated in five consecutive seasons under the leadership of Roland De Vaux of the Jerusalem-based École Bibliques (1951-1956). Eventually, 10 more caves were discovered in the area of Qumran, Cave 4 alone yielding fragments of nearly 600 manuscripts.3

The laborious task of deciphering, editing, and publishing the Dead Sea Scrolls is a drama unto itself. The original scholars entrusted with the task of publishing the Scrolls were exclusively Christian, and thus the interests of early researchers tended toward Christian backgrounds and the relationship of the Scrolls to the New Testament. This fact irked many non-Christian scholars, especially the Israelis. With the additions of Israeli scholars Elisha Qimron and Emanuel Tov to the publication team in the 1980s, this problem was rectified, and now scholars from all backgrounds work on the Dead Sea Scrolls.

In addition to the racial issues, the early publishing team was small and very slow to do their work. Between 1950 and 1990 only seven of the eventual 40 volumes in Oxford University Press’s Discoveries in the Judean Desert series had been completed. In the 1990s alone, however, 20 additional volumes in this series appeared. There are two reasons for the proliferation in publication: First, Emanuel Tov of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem became the general editor of the series in late 1990. His appointment followed an anti-Semitism scandal that resulted in then-director John Strugnell of Harvard University being removed from the post. The scandal was provoked by Strugnell’s comments in the Israeli newspaper, Ha-aretz.4

Second, Ben Zion Wachholder of Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Ohio, with the help of his student, Martin Abegg, produced a nearly complete text of the Scrolls from a previously published concordance.5 With the early use of computer databasing, Abegg was able to reverse-engineer the text of many Scrolls from the concordance. Although their publication was unauthorized both by the Israel Antiquities Authority and Oxford University, all agree their publication broke the hold on the Dead Sea Scrolls, and encouraged scholars to complete the work of official publication.6 Today all of the discovered, decipherable Scrolls have been published, and photographs of many of the Scrolls are available on the Internet.

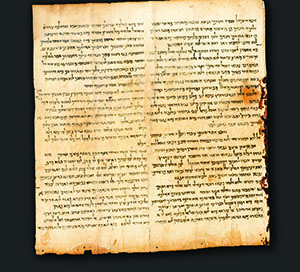

This article provides two examples. Figure 1 is a photograph of two columns of the Great Isaiah Scroll, featuring Isaiah 53. This scroll is among the best preserved, and is not typical of the discovered manuscripts. Figure 2 is a more typical collection of fragments pieced together by specialists. Most of the Dead Sea Scrolls are, indeed, not so much scrolls as scraps.

|

|

| Figure 1: The Great Isaiah Scroll ( ISaiah 53) | Figure 2: A Portion of the Temle Scoll |

The Non-Biblical Manuscripts of the Dead Sea Scrolls

It surprises many people to hear the majority of the Dead Sea Scrolls are non-biblical. Of the approximately 930 scrolls discovered in the Judean desert, only 222 are biblical (i.e., less than 25%). The percentage of biblical scrolls is much higher at Judean desert sites other than Qumran. The biblical texts of Masada, for example, represent 47% of the total number of scrolls discovered.7 We may conclude Jews living in desert communities read many different books, and were not readers of the Bible alone. This does not necessarily mean, however, that secular books were read more than the Bible. In my personal library I have hundreds of books, but my Bibles take up only about a shelf and a half. Most of these books I do not read regularly, but my Bibles are in constant use. A similar situation might have existed for the Dead Sea communities. Still, the non-biblical Scrolls have relevance for how the Old Testament was understood and interpreted by some Jews prior to the time of the New Testament.

In order to better examine the non-biblical Scrolls, further classification is needed. So we shall first discuss works most certainly not written by members of the Qumran community, what Protestants might term “Apocrypha” as well as the so-called “Pseudepigrapha.” Then we shall turn to the “sectarian texts” that were either written by members of the Qumran sect or were formative for their development as a community.

Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha

The term “apocrypha” is a Greek plural substantive meaning “things hidden.” The term is borrowed from the Church Fathers who used it frequently to refer to books outside of the canon of Scripture recognized by the church. The term “pseudepigrapha,” by contrast, properly refers to writings “falsely ascribed.” Based on this meaning, the term pseudepigrapha ought to be applied to books such as 1 Enoch (which was not written by the real Enoch), the Wisdom of Solomon (not written by Solomon), and so on. But the collection commonly called Pseudepigrapha now stands for almost any non-canonical book that does not belong to the Old Testament or to the Protestant “Apocrypha.”

Of the Catholic Church’s “deuterocanonicals” (in Protestant terms, “Apocrypha”), the Dead Sea Scrolls preserve five copies of Tobit, three of the Wisdom of Jesus ben Sirah (Ecclesiasticus), and one of the so-called Epistle of Jeremiah (not actually written by Jeremiah). The position of the Pseudepigrapha is much better. The mysterious book of 1 Enoch is represented in 12 copies from Qumran, and the book of Jubilees in no less than 13 and possibly as many as 16 copies (depending on whether the fragments represent additional manuscripts). There are also at least five additional compositions related to Jubilees, further attesting its importance. By manuscript count alone, Jubilees is better represented than all but four of the canonical Old Testament books (Psalms, Deuteronomy, Isaiah, and Genesis). Some scholars have suggested that both 1 Enoch and Jubilees were accepted as canonical Scripture in Qumran. This is certainly possible, although perhaps it is best to leave the question open. Popularity does not require canonicity (see more below).

Sectarian Texts

The Dead Sea Scrolls discovery unveiled many works that were previously unknown. Since they are associated exclusively with the Qumran sect, they are normally called “sectarian.” Indeed, some of these works relate specifically to life in the sectarian community. The most important are the Damascus Document (CD) and the Rule of the Community (1QS), which best inform us about life in the community. Other texts are legal in nature, such as the Temple Scroll (11QT) and miksat ma‘asei ha-Torah (4QMMT), roughly translated “some matters of the Law.” This latter text lists grievances the Qumran community had with the Temple and its officials in Jerusalem.

It will surprise many readers to know that some of the Qumran scrolls were written in “cryptic scripts.” Scholars believe these scripts are, in fact, based on the Hebrew language, but have never deciphered them.8 The original editor of these texts distinguished three different cryptic scripts: “Cryptic A,” “Cryptic B,” and “Cryptic C,” respectively. As far as we know, these cryptic scripts are used nowhere else. But they were in prominent use at Qumran. The leader of the Qumran community (the maskil, or “understanding one”) most likely communicated in Cryptic A himself, which represents no less than 55 manuscripts. Cryptic B is found in two manuscripts, and the text of origin remains undeciphered. Cryptic C is found in only one manuscript. It utilizes the paleo-Hebrew alphabet and five additional letters that cannot be identified. The individual who manages to decipher these cryptic scripts will earn lasting fame in the pantheon of scholarship!

More relevant for the text of the Old Testament and how we got the Bible are two categories of writings: the so-called works of rewritten Bible and the commentaries (pesharim, or “interpretations”). Geza Vermes coined the term “rewritten Bible” to refer to Jewish works written in either Hebrew or Aramaic that paraphrase the Scriptures, and insert their own expansions and interpretations.9 He primarily had in mind the book of Jubilees, the so-called Genesis Apocryphon (1QapGen), and Pseudo-Philo’s “Book of Biblical Antiquities.” The former two works were found among the Qumran scrolls.

These works of “rewritten Bible” are interpretive expansions of biblical literature. We learn many details, such as the name of Noah’s wife (“Emzara,” according to Jubilees 4:33), the reason why God chose Abram (he refused to participate in the building of the Tower of Babel, Pseudo-Philo chapter 6), and how Abram convinced Sarai to mislead about being his wife (he dreamt prophetically that she would save him, 1QapGen column 19). There is no indication that any of these expansions are to be accepted as legitimate, but they do teach us the ancient Hebrews were careful and inquisitive readers of the Bible. More importantly for us, the close following of the biblical text confirms that their Scriptures followed the exact storyline as ours. There is no evidence that the Bible has undergone massive changes over time, as some wish to allege. We read essentially the same Bible as they did.

The Old Testament Manuscripts of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The most celebrated of the Scrolls have been the Old Testament manuscripts. Although some scholars have asserted that fragments of certain New Testament verses can be located, most scholars agree that no New Testament copies, quotations, or fragments exist among the Dead Sea Scrolls.While the Qumran community did in fact exist at the time of Jesus and the Apostles, there is no evidence that any of the Dead Sea Jewish communities were aware of the early Christian movement. This means our discussion of biblical evidence must focus on the Old Testament. We shall begin by discussing the numbers of manuscripts we possess before moving to consider issues relating to the canonicity of the Old Testament.

Biblical Manuscripts by the Numbers

All Judean desert sites show a special respect for the Law of Moses. The Pentateuch represents 87 of the some 200 biblical Qumran scrolls, and 15 of the additional 25 texts discovered outside Qumran are of the Pentateuch.10 In other words, 45% of the total number of texts from the Judean desert are Pentateuchal. The Major Prophets represent 46 additional manuscripts, and the Minor Prophets 10 more. So Prophetic books account for nearly one-quarter of the whole. This leaves 25-30% for the rest of the Old Testament.

The Historical Books did not fare as well, with only 18 copies. To illustrate, just one small fragment about the size of a human hand represents all of 1 and 2 Chronicles, and no copies were identified of the Nehemiah section of Ezra-Nehemiah (which is a single book in Hebrew) or of the book of Esther. The Poetic Books, excluding Psalms, represent 14 manuscripts. But 39 manuscripts of Psalms alone were discovered, 36 of which are from Qumran. Broadly speaking, the popularity and dispersion of biblical scrolls in the Judean Desert matches very closely what we observe among the books quoted in the New Testament.

Among stand-alone books at Qumran, Psalms takes the crown (39 manuscripts), followed by Deuteronomy (33), Genesis (24), Isaiah (22), and Exodus (18). Interestingly, four of these five books were in the “top five list” of books quoted by Jesus: Psalms (11), Deuteronomy (10), Isaiah (8), and Exodus (7). In fact, Table 1 compares the number of Qumran manuscripts with the frequency of explicit quotation in the New Testament. Although books can be used without necessarily being quoted, Table 1 provides an interesting point of comparison.

| Biblical Book | Judean Desert Manuscripts |

New Testament Quotations |

| Psalms | 39 | 69 |

| Deuteronomy | 33 | 32 |

| Genesis | 24 | 24 |

| Isaiah | 22 | 51 |

| Exodus | 18 | 31 |

| Leviticus | 17 | 12 |

| Numbers | 11 | 1 |

| Minor Prophets | 10 | 25 |

| Daniel | 8 | 0 |

| Jeremiah | 6 | 4 |

| Ezekiel | 6 | 0 |

| Job | 6 | 1 |

| 1–2 Samuel | 4 | 3 |

| Ruth | 4 | 0 |

| Song of Songs | 4 | 0 |

| Lamentations | 4 | 0 |

| Judges | 3 | 0 |

| 1-2 Kings | 3 | 3 |

| Joshua | 2 | 1 |

| Proverbs | 2 | 5 |

| Ecclesiastes | 2 | 0 |

| Ezra | 1 | 0 |

| 1-2 Chronicles | 1 | 0 |

| Nehemiah | 0 | 1 |

| Esther | 0 | 0 |

| Table 1: Number of Dead Sea Scrolls by biblical book compared with New Testament quotations by biblical book11 | ||

The Biblical Manuscripts and the Old Testament Canon

So far we have discussed mostly facts. But what do these facts mean? It is prudent to remember that absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence. In other words, if certain books are missing (such as Esther or Nehemiah) or are poorly represented (such as Chronicles or Ezra) among the Dead Sea Scrolls, we cannot on that basis alone conclude that the Qumran community rejected them from their biblical canon. And the opposite is true: if certain books are well represented among the Dead Sea Scrolls (such as Jubilees or 1 Enoch), we cannot on that basis alone conclude that the Qumran community accepted them into their biblical canon. What books people like to read and what books people consider inspired may, in fact, be different. We know from modern experience that certain books of the Bible are underappreciated and undertaught among Christians. Do we wish to exclude these books from the canon? Of course not. Again, popularity is not the same thing as canonicity.

The truth is that the Dead Sea Scrolls are of limited value in answering Old Testament questions of canonicity. They apparently did not think in those terms, and never addressed the question of which books were in and which ones were out. The better question is to ask what the Qumran sectarians considered authoritative. And in order to answer this question, we must move beyond simply counting manuscripts. We must attempt to understand how the biblical literature was used.

We shall start with the name of “Moses,” which occurs over 150 times in the sectarian manuscripts. All sections of the Pentateuch are quoted and interpreted as inspired literature. This should not surprise us, for the Pentateuch was the most popular portion of the Bible among all Jewish groups at the time of Jesus. But we can go further. The text of the Prophets is equally authoritative. The Pesher Habakkuk is a commentary that takes the book of Habakkuk as an inspired prophecy of the experiences of the Qumran community, and is interpreted clearly in this fashion. Other prophets, such as Isaiah and Ezekiel, are also quoted as authorities. While we cannot regard all of the prophets as equally authoritative based on the way they are quoted (Obadiah, for instance, is never quoted in this way), most of them can be regarded as both inspired and authoritative.

“David,” too, appears frequently as a sacred figure. The Qumran sectarians know the details of his life from Samuel and Chronicles. For example, “David’s actions ascended as the smoke of a sacrifice [before God] except for the blood of Uriah, but God forgave him” (CD 5.5–6). Such high estimation of David’s character explains how the Psalms he wrote would be considered authoritative. And the Psalms are frequently quoted as inspired in the Dead Sea Scrolls. In fact, the Old Testament as a whole can be characterized as “the Law, the Prophets, and David” (4QMMT fr. 14). Since the Hebrew Bible is generally divided into three parts—the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings—this threefold division is extremely important. Jesus’ own division of the Old Testament into “the Law, the Prophets, and the Psalms” is very similar (Luke 24:44).

Interestingly, although many books and parts of the Old Testament are quoted as authoritative, to my knowledge Jubilees, 1 Enoch, and none of the other Apocryphal or Pseudepigraphical books found among the Dead Sea Scrolls are quoted in this way. The sectarians may have borrowed language and ideas from these books, and may have been heavily influenced by their teachings, but they did not consider them on par with the books of the Old Testament. If these secondary books were considered in any sense authoritative, they appear never to be quoted as such and thus used as the basis for doctrine. This is telling. We can compare the situation to the role of a preacher in a church. Generations of congregants may know the preacher’s retelling of the Bible better than they know the Bible itself! Yet when asked if they consider their preacher as a voice on par with the authority of Scripture, they would likely reply with an indignant, “Of course not!” Acknowledged authority may well be different from unrealized influence.

The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Reliability of the Biblical Text

There is no doubt that the Bible has been transmitted faithfully to us through the centuries, and that the Dead Sea Scrolls further help to substantiate that truth. Some biblical apologists, however, have often exaggerated the “confirmation” the Dead Sea Scrolls offer the text of the Old Testament. Such comments are often made on the basis of the Great Isaiah Scroll alone, and are sometimes unwisely connected to a percentage evaluation. For example, I have heard several times, “the Dead Sea Scrolls confirm the text of the Old Testament in 99% of the cases.” Not only is such a figure untrue, this whole line of assertion paints an unrealistic picture of the evidence. First, most of the biblical Scrolls, as we have seen, are extremely fragmentary, and therefore cannot offer us a clear basis of comparison for the Bible as a whole. In fact, the only biblical book to be preserved among the Dead Sea Scrolls intact is the Great Isaiah Scroll. Even in the Pentateuch and the Psalms, where the evidence is good, whole sections of the biblical text are completely missing or extremely lacunose. In these cases, the Scrolls cannot confirm anything. And we are speaking here of the best-preserved books. The situation is worse for the other biblical books.

Second, many apologists exaggerate the similarities and ignore the differences between the texts that can be compared. For example, the traditional Hebrew Bible preserved in the two major Medieval manuscripts, the Aleppo and Leningrad Codices, respectively (the so-called Masoretic Text), fixes the height of Goliath as “six cubits and a span” (1 Samuel 17:4). But 4QSama, a Dead Sea Scrolls manuscript dating to the first century B.C., reads in this passage “four cubits and a span.” This means Goliath is about six feet, four inches tall instead of the Masoretic text’s gigantic nine feet, four inches tall. Further, the reading of 4QSama agrees with the translation of the Greek Old Testament, which read “four cubits and a span” well before the time of the Medieval manuscripts. Should we revise the height of Goliath in our Bibles? Most modern translations have chosen either to ignore our oldest Hebrew copy of this portion of Samuel, or to relegate the information to a footnote. Why?

Another example from Samuel can be located in a mysterious passage. The traditional Masoretic text has it as follows: “Then Nahash the Ammonite came up and encamped against Jabesh Gilead; and all the men of Jabesh said to Nahash, ‘Make a covenant with us, and we will serve you.’ And Nahash the Ammonite answered them, ‘On this condition I will make a covenant with you, that I may put out all your right eyes, and bring reproach on all Israel’” (1 Samuel 11:1-2, NKJV). Nowhere else in the Bible or in ancient Near Eastern literature do we read eye-gouging as a covenantal condition. This passage is exceedingly strange and impossible to explain. But if we look at the oldest Hebrew copy of Samuel, we gain a bit more clarity.

The NRSV is one of the few modern versions to use the text of 4QSama in their translation of this passage. As a prelude to 1 Samuel 11:1, the NRSV includes the words,

Now Nahash, king of the Ammonites, had been grievously oppressing the Gadites and the Reubenites. He would gouge out the right eye of each of them and would not grant Israel a deliverer. No one was left of the Israelites across the Jordan whose right eye Nahash, king of the Ammonites, had not gouged out. But there were seven thousand men who had escaped from the Ammonites and had entered Jabesh-gilead.

This note, found in the oldest Hebrew manuscript of Samuel, explains two important details. First, it explains the demand for the right eyes of the Reubenites and Gadites. Second, it explains why the men fled to Jabesh-Gilead and why Nahash besieged it. Not only is this reading in the oldest Hebrew copy of Samuel, it actually aids our understanding of the Bible. Yet most modern English translations reject it.

One more example shall suffice. Hebrew poetry is intricately designed in ways that English readers simply cannot appreciate. One of the most complex of their poetic forms is the acrostic poem. The author will compose a coherent poem beginning each line, verse, or stanza with subsequent letters of the Hebrew alphabet from ’aleph totav. Psalm 119 is one of the most famous and indeed one of the most beautiful pieces of literature in world history. Psalm 145 is an acrostic as well. But there is one problem: a verse is missing. Psalm 145 walks through every letter of the Hebrew alphabet with the exception of the letter nun. The Greek Old Testament always had this missing line, but the later Masoretic manuscripts had lost it somewhere along the way. Alas, due to the discovery of 11QPsa, the verse can now be restored: “God is faithful in his words and gracious in all his works.”

Let us pause here to make an important observation: these cases we have been discussing are unusual. In fact, there are relatively few examples of passages that are totally different in the Dead Sea Scrolls than they appear in the Medieval Hebrew manuscripts. And the majority of the passages that are different match some other known version of the Old Testament (usually the Greek translation). This means that the Old Testament has been copied and transmitted with remarkable accuracy. It is not a stretch to say the Hebrew Bible known to Jesus is essentially the same as the one known to us. All of this leads to the conclusion that the Dead Sea Scrolls sometimes complicate, but generally confirm, our knowledge of the Old Testament text.

Conclusion

The Dead Sea Scrolls are important for a number of reasons. First, they shed light on an otherwise known Jewish group. Actually, the people who wrote the Scrolls never refer to themselves as Jews. They are intriguingly vague about their identity. Second, the Scrolls indicate that certain books of the Bible were more popular than others, a conclusion we could draw similarly from the New Testament quotations of the Old Testament.

Third, the use of the Old Testament as an authoritative source for biblical interpretation and personal and community life matches material from the New Testament as well. Finally, the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls allows us to access Old Testament manuscripts more than 1,000 years older than we previously possessed. Before the discovery of the Scrolls, the oldest complete manuscript of any Old Testament book dated to the 10th century A.D. To be clear, if Moses wrote the Pentateuch in circa 1400 B.C., then our earliest copy of his complete work in Hebrew dated 2,400 years after it was written! It is with justification that the Dead Sea Scrolls are considered by many the most important biblical archaeological discovery of all time.

Endnotes

1 The scholar who was involved in and who investigated most carefully the discovery of the early scrolls is John C. Trever. His investigation is recorded in his 1965 book, The Untold Story of Qumran (Westwood, N.J.: Revell).

2 A digital interactive copy of these scrolls can be viewed at the following address: http://dss.collections.imj.org.il.

3 A twelfth cave was discovered in 2016, but this cave yielded no manuscripts. The geology of the region has changed greatly over the past 2,000 years, and it is probable that future caves will be discovered.

4 An English language version of the Israeli reporter’s interview of Strugnell was printed in the January/February, 1991 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review, (17[1]).

5 The work of Wachholder and Abegg was published in two volumes by the editor of the Biblical Archaeology Review in Hershel Shanks, ed. (1992), A Facsimile Edition of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Washington, D.C.: Biblical Archaeology Society).

6 A detailed account of the role of Hebrew Union College may be found in Jason Kalman (2013), Hebrew Union College and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Cincinnati: HUC Press).

7 See Emanuel Tov (2002), “The Biblical Texts from the Judean Desert,” in The Hebrew Bible as Book: The Hebrew Bible and the Judean Desert Discoveries, ed. Edward Herbert and Emanuel Tov (London: The British Library), p. 141.

8 The most recent editor of these texts presents much of his work in Stephen Pfann (2000), Discovery in the Judean Desert (Oxford: Clarendon), 36:515-574.

9 Geza Vermes (1973), Scripture and Tradition in Judaism (Leiden: Brill, second edition).

10 See Emanuel Tov, “The Biblical Texts from the Judean Desert,” p. 141.

11 For the Dead Sea Scrolls, I use the table published in Flint and VanderKam (2002), The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls (San Francisco: Harper), p. 150, on whom I depend for much information in this section. For the New Testament quotations, I use the list compiled by Crossway (https://www.crossway.org/blog/2006/03/nt-citations-of-ot/).